On Intimacy: A Compendium [1]

<2020>

As one of human's innate needs, engagement in intimate interactions is essential to our health & well-being (Lomanowska 139). While this usually means direct physical closeness and proximity, widespread integration of internet & technology into the daily has opened up new ways and opportunities to experience interpersonal relations (Madianou and Miller 170). The shift of modality not only raises a question of its' reverberations on interpersonal intimacy, but also challenges the traditional interpretation, and the physicality of the term ‘to be intimate’.

This compendium aims to explore the form of these transformations in several different interpersonal relationship settings—romantic, filial, parasocial, sexual—through examination of case studies.

This compendium aims to explore the form of these transformations in several different interpersonal relationship settings—romantic, filial, parasocial, sexual—through examination of case studies.

This research compendium is a precursor to a series of projects that would culminate into the designer’s undergraduate final year project, documented separately within this portfolio site.

Bibliography

Lomanowska, Anna M., and Matthieu J. Guitton. “Online Intimacy and Well-Being in the Digital Age.” Internet Interventions, vol. 4, 16 June 2016, pp. 138–144., URL. Accessed 2 December 2021.

Madianou, Mirca, and Daniel Miller. “Polymedia: Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, 22 Aug. 2012, pp. 169–187., URL. Accessed 2 December 2021.

[2] On Intimacy: “I Think I Like You”

<2021>

In 1985, Monica Moore published a now-famous study that covertly observed, analyzed, and catalogued nonverbal facial expressions & gestures exhibited by more than 200 random women—commonly labeled as “flirting behaviors.” While there had been studies that looked into female mating preferences, their selecting mechanisms and patterns remains undefined (Moore 238). Moore’s study were to document and describe this ensemble of visual & tactile displays of courting signals.

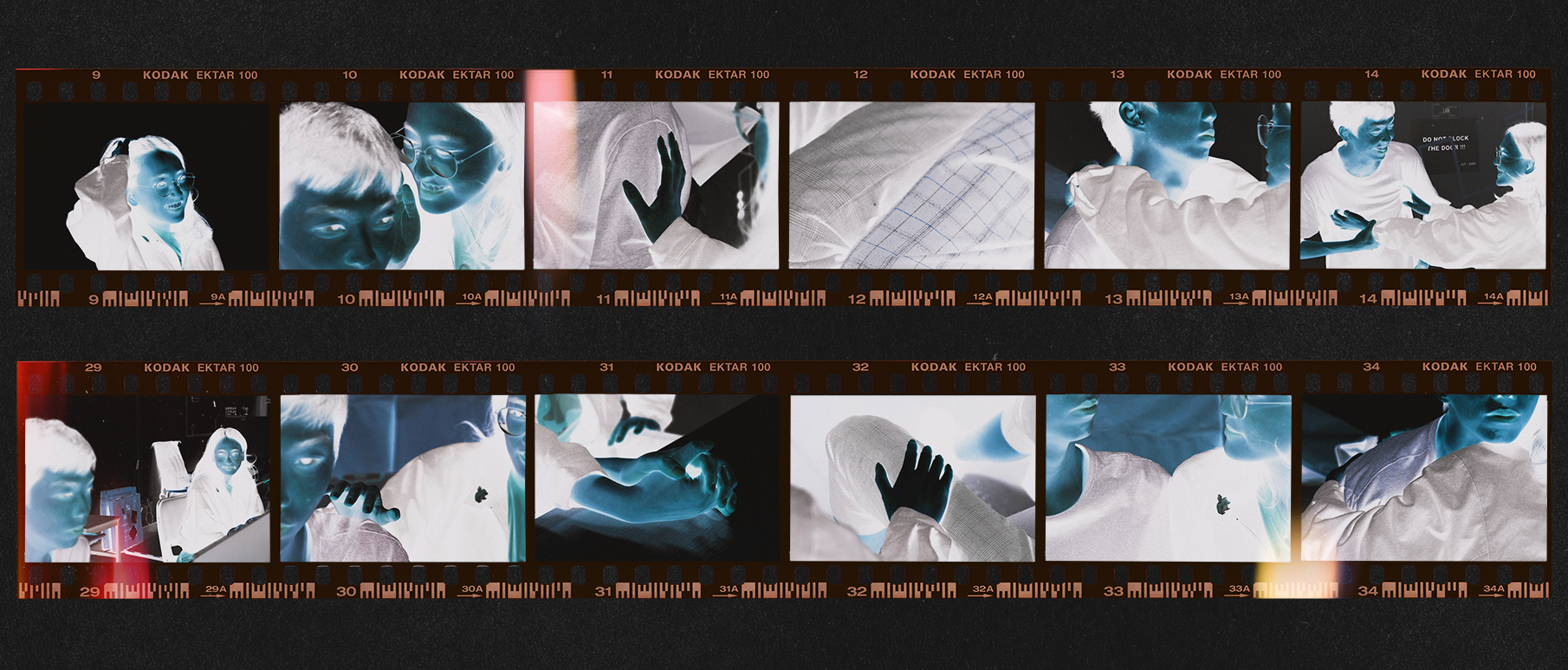

On the next installation of the ‘On Intimacy’ series, a small research photography project was done to visualize intimacy within a romantic setting. Based on a 1985 study published in the Journal of Ethology and Sociobiology, the project tries to reverse-engineer and capture the nonverbal courtship patterns catalogued in the paper, through modern photography.

While the cultural relevancy of these courtship patterns are indisputable—being the typical visual language of modern romantic films—it is important to contextualize that these cues occurs in real‑life settings only. In reality, the pervasiveness of digital dating and its multimodal property (Ramirez et al. 102) had driven (digital) natives to develop new norms & patterns of courtship as a response to the online dating discourse and internet milieus.

Bibliography

Drouin, Michelle, et al. “Why Do People Lie Online? ‘Because Everyone Lies on the Internet.’” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 64, Nov. 2016, pp. 134–142., URL. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Ellison, Nicole, et al. “Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 11, no. 2, 2006, pp. 415–441., URL. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Finkel, Eli J., et al. “Online Dating: A Critical Analysis From the Perspective of Psychological Science.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest, vol. 13, no. 1, 2012, pp. 3–66., URL. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Manning, Jimmie. “Construction of Values in Online and Offline Dating Discourses: Comparing Presentational and Articulated Rhetorics of Relationship Seeking.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 19, no. 3, 2013, pp. 309–324., URL. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Moore, Monica M. “Nonverbal Courtship Patterns in Women.” Ethology and Sociobiology, vol. 6, no. 4, 30 July 1985, pp. 237–247., URL. Accessed 5 December 2021.

Ramirez, Artemio, et al. “When Online Dating Partners Meet Offline: The Effect of Modality Switching on Relational Communication Between Online Daters.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 20, no. 1, 2014, pp. 99–114., URL. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Code Authorship Attribution

The source code of the above’s comparison slider feature is based on Image Comparison Slider by Mario Duarte (2021).

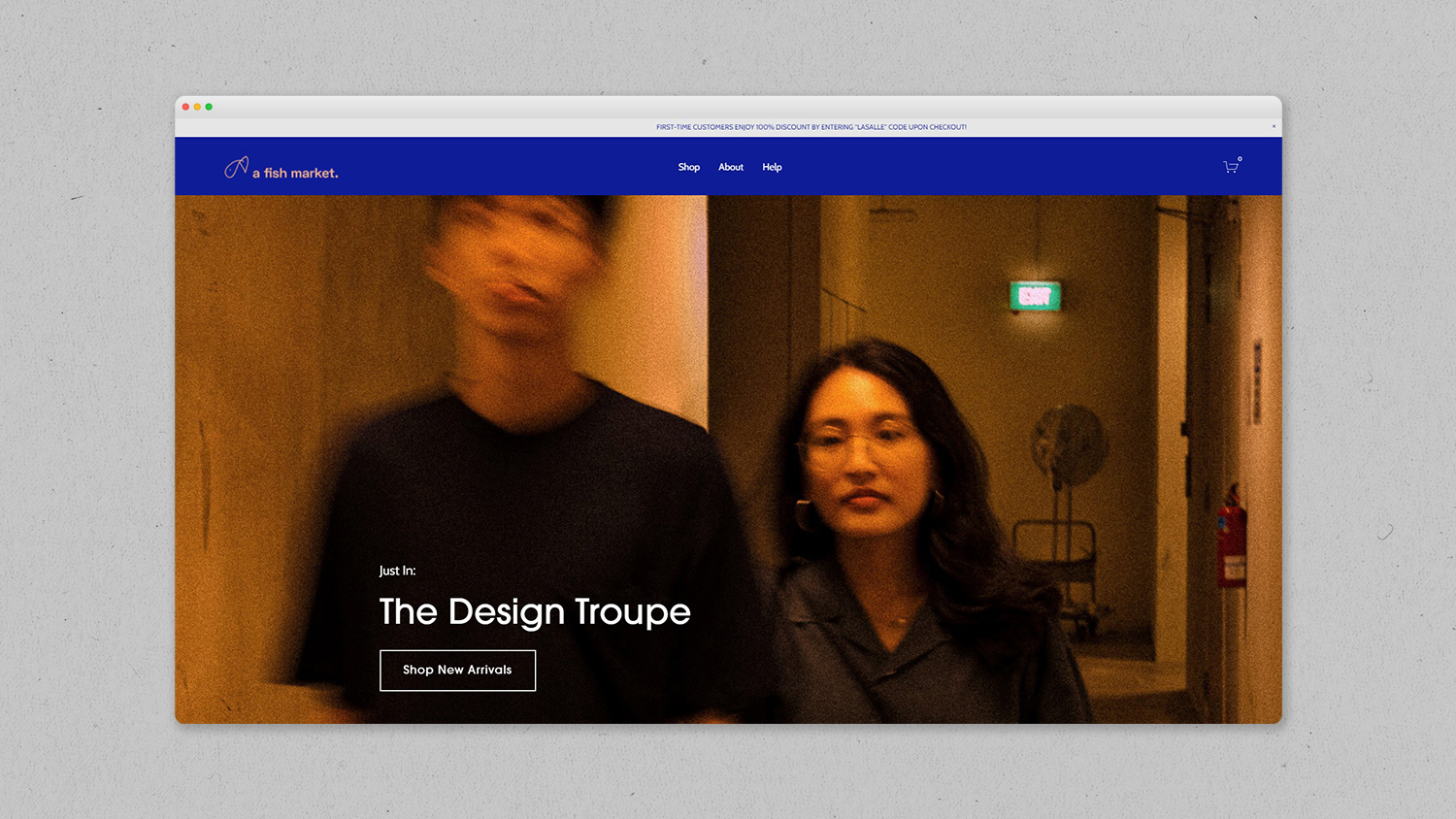

[3] On Intimacy: A Fish Market

<2021>

Summary

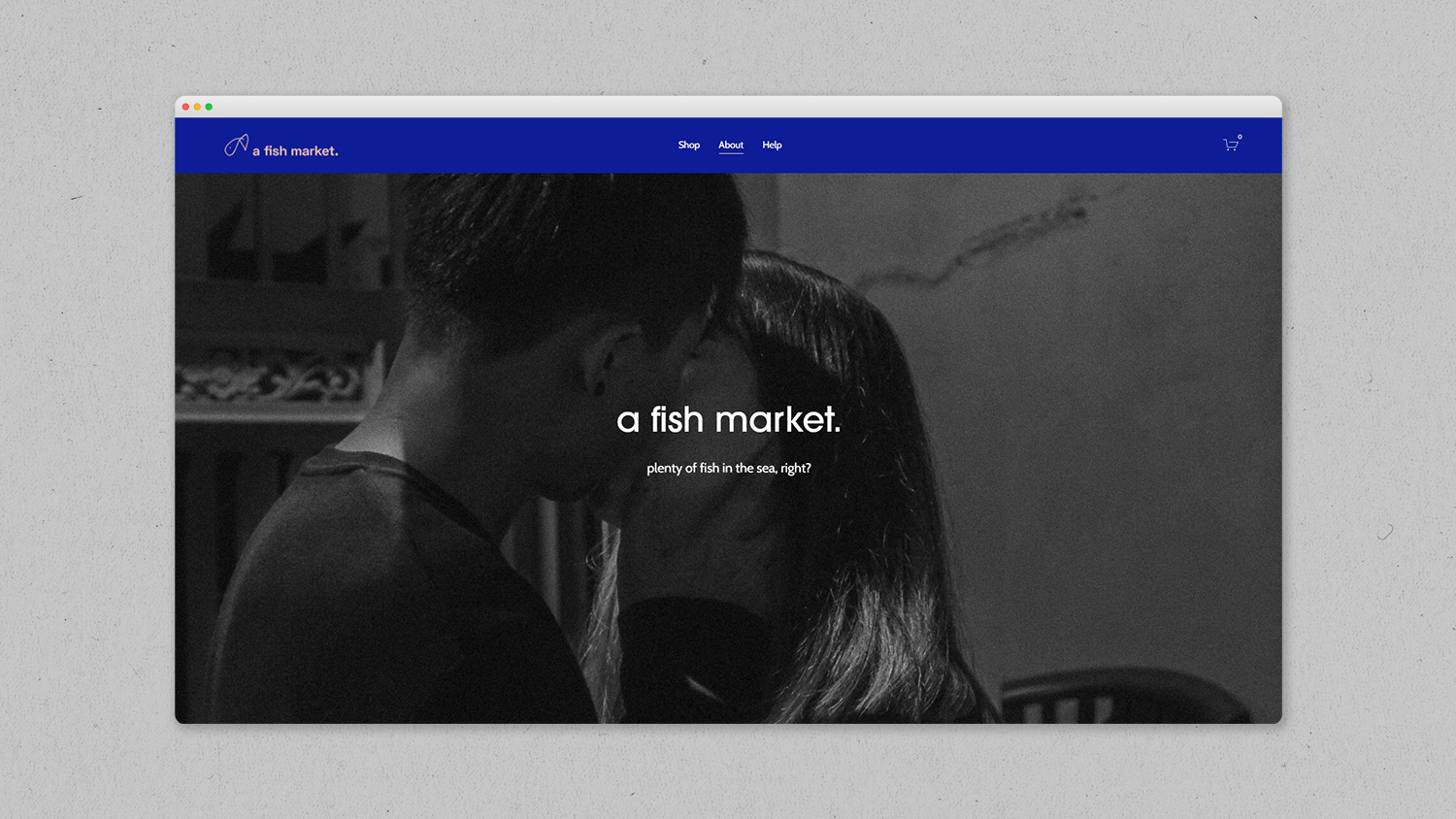

A Fish Market is a satirical design project that looks into the online dating discourse from the lens of consumerism & material culture; highlighting the shift of intimacy and commodification of people in the dating ‘marketplace’.

A Fish Market is a satirical design project that looks into the online dating discourse from the lens of consumerism & material culture; highlighting the shift of intimacy and commodification of people in the dating ‘marketplace’.

Keywords

Consumerism

Market metaphor

Online dating

Relationshopping

Self‑presentation

Consumerism

Market metaphor

Online dating

Relationshopping

Self‑presentation

Departing from the theme of intimacy and courtship, the final installation of the ‘On Intimacy’ series finds itself reflecting on the digital dating discourse. A Fish Market delivers a fully-functional shopping site that showcases humans as products; commenting upon the commodification and depersonalization of romance within the virtual space of dating apps.

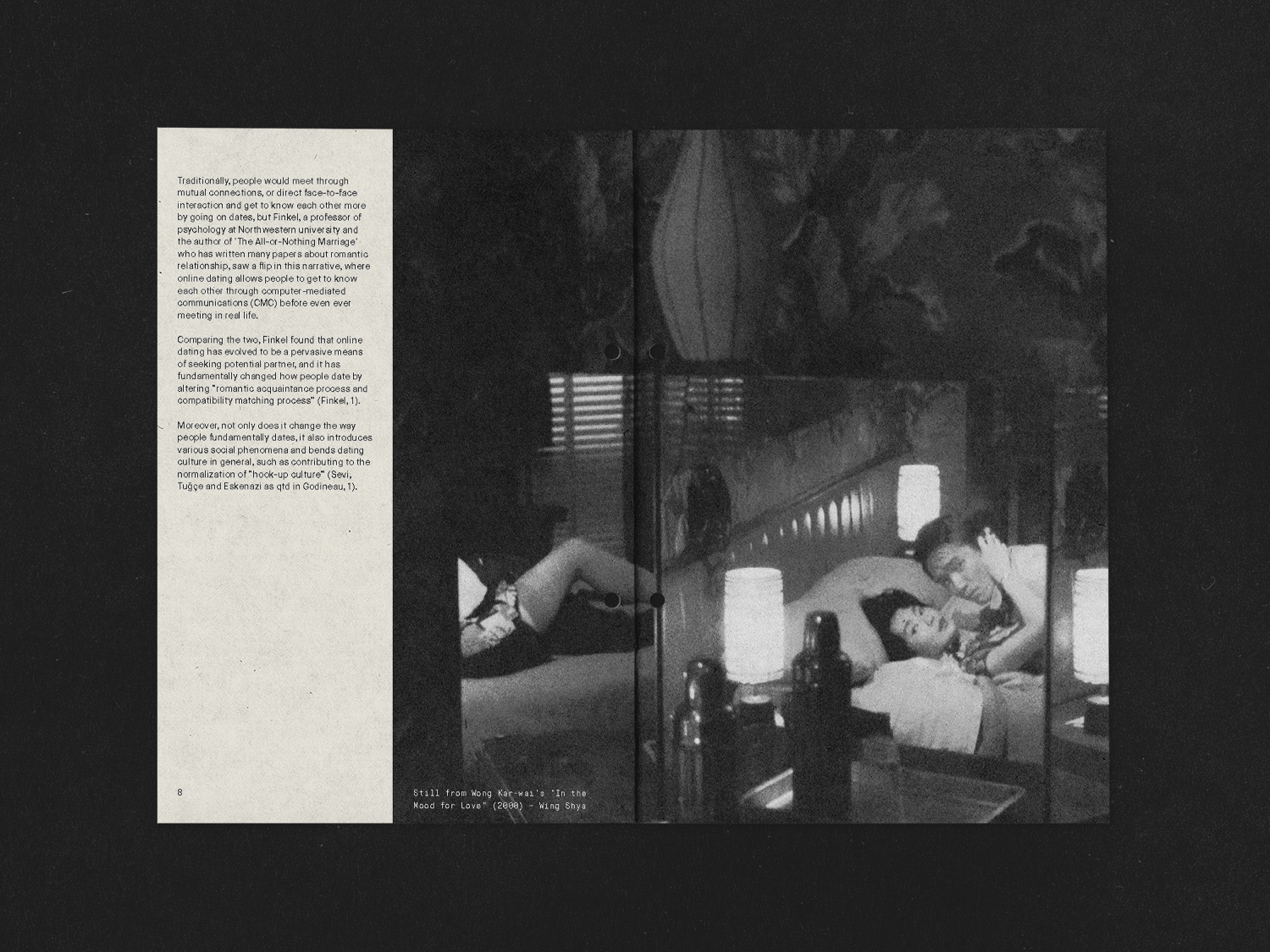

With ubiquitous access to the internet and diminished association with social stigma, online dating had undeniably shifted from a marginal to a mainstream means to meet potential partners (Ellison et al. 416).

Among the few novel qualities of online dating—such as endless number of potential dates (Finkel et al. 6, Hobbs et al. 272) and mixed-modality dating (Ramirez et al. 100)—perhaps, unique to its predecessors are the frameworks of self-presentation (Hancock et al. 450) & self-disclosure (Manning 309). The two frameworks alter the romantic acquaintance process by providing daters a broad range of (asynchronous & editable) information on potential partners before they meet face-to-face (FtF) (Finkel et al. 3).

Combined with the need to stand out in such a large pool, online daters are ipso facto incentivized to present themselves strategically, crafting deceptive and idealized profiles instead of an authentic one (Ellison et al. 424, Ward 1646), something Adam Arvidsson calls as “commodification of affect” that turns dating apps into “a metaphorical marketplace” where individuals shop each other’s profiles (qtd in Heino et al. 429).

Among the few novel qualities of online dating—such as endless number of potential dates (Finkel et al. 6, Hobbs et al. 272) and mixed-modality dating (Ramirez et al. 100)—perhaps, unique to its predecessors are the frameworks of self-presentation (Hancock et al. 450) & self-disclosure (Manning 309). The two frameworks alter the romantic acquaintance process by providing daters a broad range of (asynchronous & editable) information on potential partners before they meet face-to-face (FtF) (Finkel et al. 3).

Combined with the need to stand out in such a large pool, online daters are ipso facto incentivized to present themselves strategically, crafting deceptive and idealized profiles instead of an authentic one (Ellison et al. 424, Ward 1646), something Adam Arvidsson calls as “commodification of affect” that turns dating apps into “a metaphorical marketplace” where individuals shop each other’s profiles (qtd in Heino et al. 429).

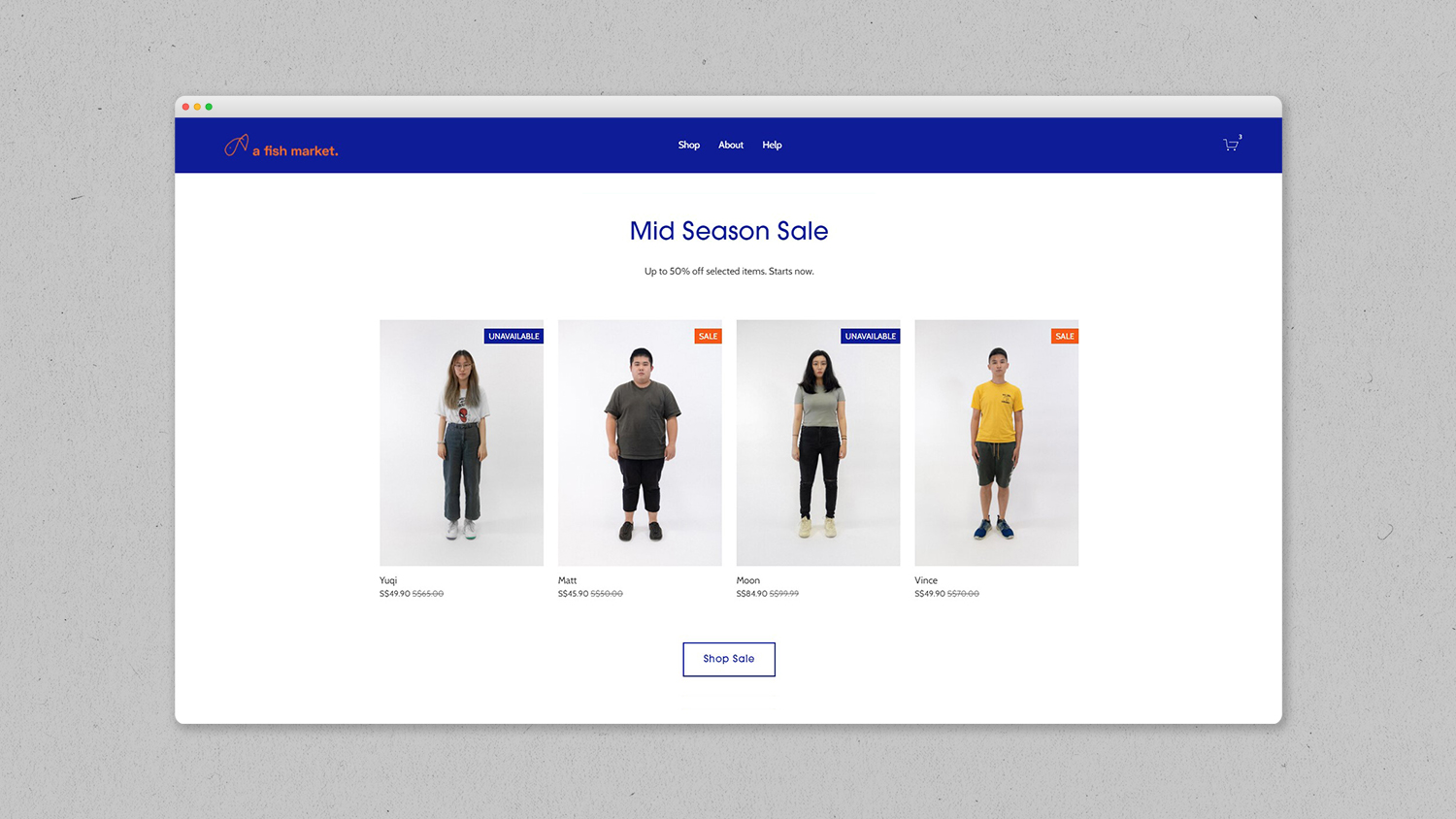

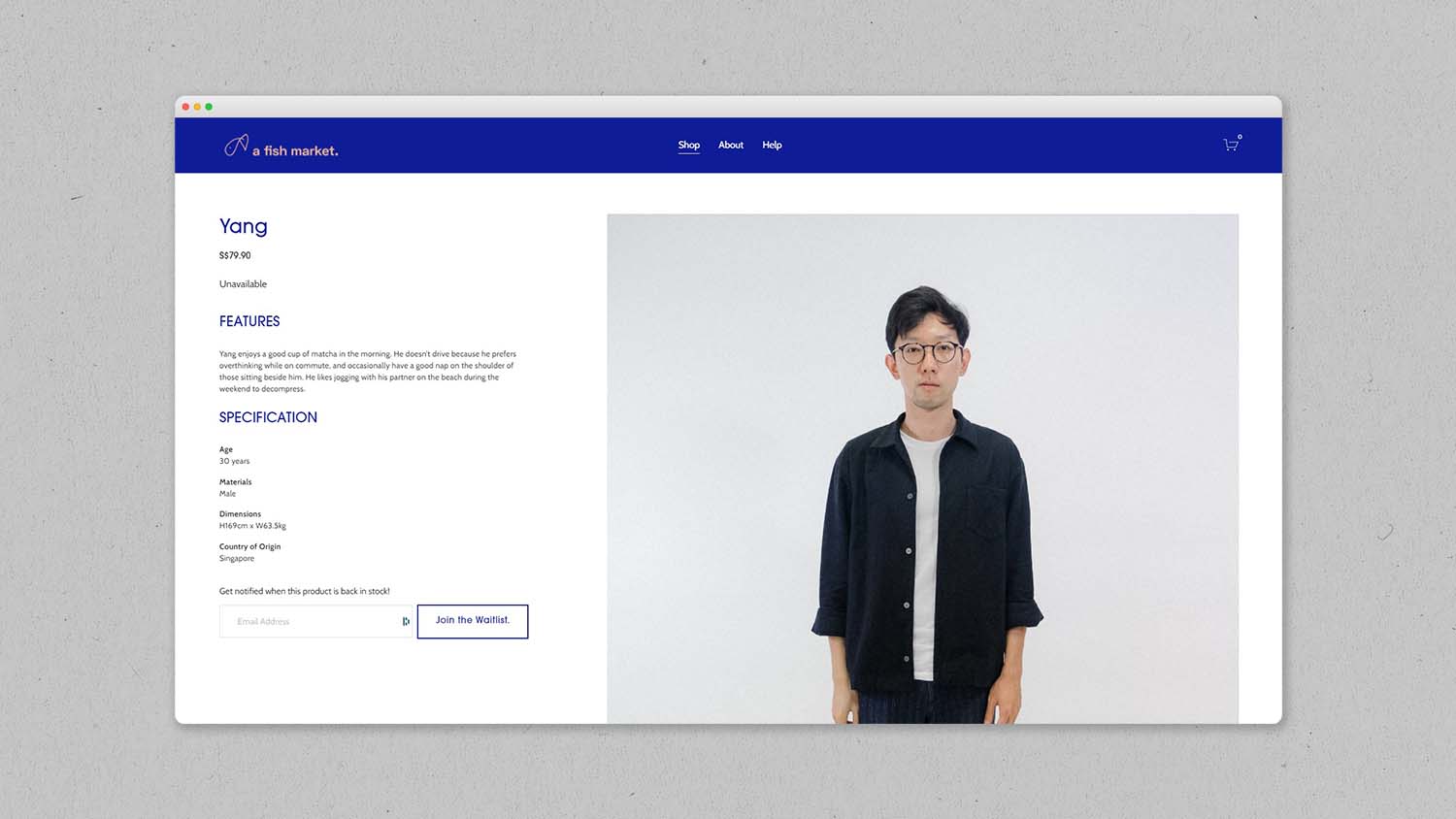

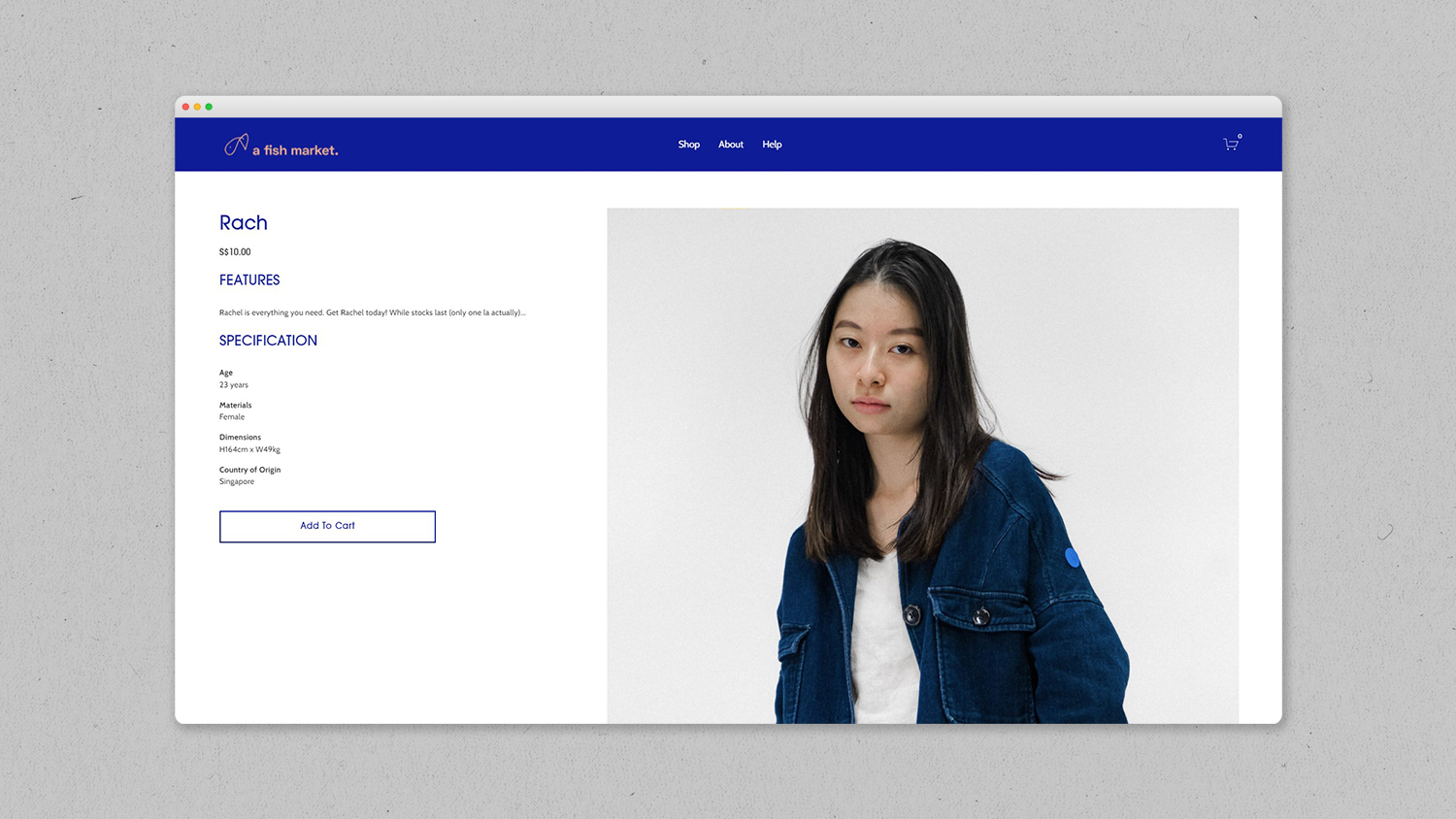

The website features a fully-functional shopping experience, from an add-to-cart function, promo codes, payment gateway, to order confirmation email. Open call were put up to source for model-volunteers, and the photoshoot lasted for a week, with over 400 frames collected at the end of the session.

Subjects were also instructed to participate in a single-blind data collection process, where they fill a few short questions (nickname, age, height, etc.) The data were processed in CSV using formulas to generate ‘product’ information that is fed into Squarespace’s Commerce API.

As an example, the models’ relationship status corresponds to their stock availability, and their price-value were derived from a question that asked the models to self-rate their attractiveness in numbers of 0.0-100.0.

Subjects were also instructed to participate in a single-blind data collection process, where they fill a few short questions (nickname, age, height, etc.) The data were processed in CSV using formulas to generate ‘product’ information that is fed into Squarespace’s Commerce API.

As an example, the models’ relationship status corresponds to their stock availability, and their price-value were derived from a question that asked the models to self-rate their attractiveness in numbers of 0.0-100.0.

Re material culture, intimacy, and the pandemic, Hardon prompted us to think more about the physical objects we bring into our lives and the story we connect to them to end the cycle of consumerism & materialism, during a Dutch Design Week symposium.

Similarly, A Fish Market provokes modern daters to rethink and reflect on their ‘relationshopping’ habit. It invites online daters to reconcile intimacy into the modality through the practice of mindfulness. After all, we want to date the person, not the persona.

Similarly, A Fish Market provokes modern daters to rethink and reflect on their ‘relationshopping’ habit. It invites online daters to reconcile intimacy into the modality through the practice of mindfulness. After all, we want to date the person, not the persona.

Bibliography

Ellison, Nicole, et al. “Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 11, no. 2, 17 July 2006, pp. 415–441., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Finkel, Eli J., et al. “Online Dating: A Critical Analysis From the Perspective of Psychological Science.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest, vol. 13, no. 1, 7 Mar. 2012, pp. 3–66., URL. Accessed 12 January 2021.

Hancock, Jeffrey T., et al. “The Truth about Lying in Online Dating Profiles.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 29 Apr. 2007, pp. 449–452., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Heino, Rebecca D., et al. “Relationshopping: Investigating the Market Metaphor in Online Dating.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 27, no. 4, 9 June 2010, pp. 427–447., URL. Accessed 18 March 2021.

Hobbs, Mitchell, et al. “Liquid Love? Dating Apps, Sex, Relationships and the Digital Transformation of Intimacy.” Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 2, 5 Sept. 2016, pp. 271–284., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

“Live Talk with Dutch Design Week about Our Relationship with Products.” YouTube, Dezeen, 20 Oct. 2020, URL. Accessed 24 March 2021.

Manning, Jimmie. “Construction of Values in Online and Offline Dating Discourses: Comparing Presentational and Articulated Rhetorics of Relationship Seeking.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 19, no. 3, 1 Apr. 2014, pp. 309–324., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Meredith, Brooke. “‘Relationshopping’ Is Ruining Romance.” Medium, Soul Stirring Love, Rockin’ Relationships, and a Life Most Fulfilled, 1 Sept. 2020, URL. Accessed 3 January 2022.

Ramirez, Artemio, et al. “When Online Dating Partners Meet Offline: The Effect of Modality Switching on Relational Communication between Online Daters .” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 20, no. 1, 17 Sept. 2014, pp. 99–114., URL. Accessed 18 January 2022.

Ward, Janelle. “What Are You Doing on Tinder? Impression Management on a Matchmaking Mobile App.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, 6 Nov. 2016, pp. 1644–1659., URL. Accessed 8 March 2021.

Ellison, Nicole, et al. “Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 11, no. 2, 17 July 2006, pp. 415–441., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Finkel, Eli J., et al. “Online Dating: A Critical Analysis From the Perspective of Psychological Science.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest, vol. 13, no. 1, 7 Mar. 2012, pp. 3–66., URL. Accessed 12 January 2021.

Hancock, Jeffrey T., et al. “The Truth about Lying in Online Dating Profiles.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 29 Apr. 2007, pp. 449–452., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Heino, Rebecca D., et al. “Relationshopping: Investigating the Market Metaphor in Online Dating.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 27, no. 4, 9 June 2010, pp. 427–447., URL. Accessed 18 March 2021.

Hobbs, Mitchell, et al. “Liquid Love? Dating Apps, Sex, Relationships and the Digital Transformation of Intimacy.” Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 2, 5 Sept. 2016, pp. 271–284., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

“Live Talk with Dutch Design Week about Our Relationship with Products.” YouTube, Dezeen, 20 Oct. 2020, URL. Accessed 24 March 2021.

Manning, Jimmie. “Construction of Values in Online and Offline Dating Discourses: Comparing Presentational and Articulated Rhetorics of Relationship Seeking.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 19, no. 3, 1 Apr. 2014, pp. 309–324., URL. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Meredith, Brooke. “‘Relationshopping’ Is Ruining Romance.” Medium, Soul Stirring Love, Rockin’ Relationships, and a Life Most Fulfilled, 1 Sept. 2020, URL. Accessed 3 January 2022.

Ramirez, Artemio, et al. “When Online Dating Partners Meet Offline: The Effect of Modality Switching on Relational Communication between Online Daters .” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, vol. 20, no. 1, 17 Sept. 2014, pp. 99–114., URL. Accessed 18 January 2022.

Ward, Janelle. “What Are You Doing on Tinder? Impression Management on a Matchmaking Mobile App.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, 6 Nov. 2016, pp. 1644–1659., URL. Accessed 8 March 2021.

Seabank

<2020>

Introduction

Seabank is a digital banking arm of Sea Ltd that came about from an M&A deal between Shopee and Bank BKE Indonesia. This project is a speculative exercise stemming from an internal branding project to explore the possibilities of brand direction.

Seabank is a digital banking arm of Sea Ltd that came about from an M&A deal between Shopee and Bank BKE Indonesia. This project is a speculative exercise stemming from an internal branding project to explore the possibilities of brand direction.

The proposed brand direction embraces a bold, expressive energy, targeting digital natives with confidence and relevance. Visually, it draws from Gen Z culture — trend-conscious, socially fluent, and unapologetically vibrant — while maintaining a grounded sense of trust and polish expected of a financial institution.

Seabank positions itself at the intersection of convenience, technology, and youth culture. Designed to serve digital-first users across Indonesia, its identity needed to convey both immediacy and trust. The logo captures this balance — expressive in spirit, grounded in form.

The outer shape of the logo takes inspiration from Sea Group’s corporate mark — a stylized wave that evokes motion, continuity, and digital liquidity. This reference roots Seabank within the larger brand ecosystem while expressing adaptability and flow, both essential traits for a digital-first financial platform.

Nested at the core is a diamond-like form, symbolizing value, stored currency, and the role of Seabank as a modern steward of finance. It reflects a treasury in abstraction — a secure digital token at the heart of movement and exchange. Colored in Shopee’s signature orange, the mark also serves as a quiet nod to Seabank’s strategic role within Sea Group’s wider ecosystem.

The brand was developed with a deep understanding of the Indonesian fintech landscape and Gen Z user behaviors. Rather than default to surface-level design trends, the approach prioritized resonance: how the brand feels, speaks, and behaves within real-life usage. Extensive audience research informed the tone, color choices, and touchpoints — resulting in a brand identity built not just to look appealing, but to be culturally and functionally relevant.

The primary brand color draws from Shopee’s signature orange, creating seamless alignment across Sea Group’s ecosystem. A supporting palette of off-white, charcoal grey, and black provides balance, offering flexibility across both light and dark environments.

General Grotesque was selected as the brand’s typeface for its contemporary geometry, legibility, and character. It balances modern digital utility with a touch of editorial sharpness — appropriate for both interface design and brand communications.

While the brand lives primarily in digital formats, a visual system for physical stationery was developed to demonstrate adaptability. The applications remain clean, structured, and restrained — extending the identity into print with clarity and coherence.

The advertising visuals extend Seabank’s identity across campaign touchpoints — bold layouts, punchy copy, and striking color usage ensure high visibility in digital and urban contexts. These mockups demonstrate how the brand holds a strong, recognizable voice across formats, from mobile banners to street posters, all while remaining true to its audience-first strategy.

The advertising visuals extend Seabank’s identity across campaign touchpoints — bold layouts, punchy copy, and striking color usage ensure high visibility in digital and urban contexts. These mockups demonstrate how the brand holds a strong, recognizable voice across formats, from mobile banners to street posters, all while remaining true to its audience-first strategy.

Advertising concepts further define Seabank’s voice: energetic, personable, and audience-aware. The campaign visuals deliver clear value messaging with youthful boldness — positioning Seabank not only as a product, but as a relatable digital lifestyle brand.

This speculative rebrand was presented to the design leadership at Shopee during the internship wrap-up, where it was well received for its insight into the Indonesian market and its creative alignment with younger users. While not an official direction, the project served as an imaginative proposal for how Seabank could evolve with its audience in mind.

Reuters Staff. “Indonesian Banking Regulator Says Sea Group’s Shopee Acquires Bank BKE.” Reuters, 18 Feb. 2021, URL. Accessed 27 June 2025.

Silviana, Cindy. “Sea Group Firms up Digital Payments Play in Indonesia with Bank BKE Acquisition.” DealStreetAsia, 13 Jan. 2021, URL. Accessed 29 June 2025.

Footnote

︎ The logomark for this brand was developed as a collaborative effort within the Brand Design team. Adaptation and application of the branding visuals across various touchpoints were carried out independently as part of this project.

︎ Select elements of this page, including portions of the rationale and a small number of visual mockups, were developed with the assistance of generative AI tools. All design concepts, direction, and final decisions reflect my own work and creative intent.

Sengkang Smokers

<2020>

Introduction

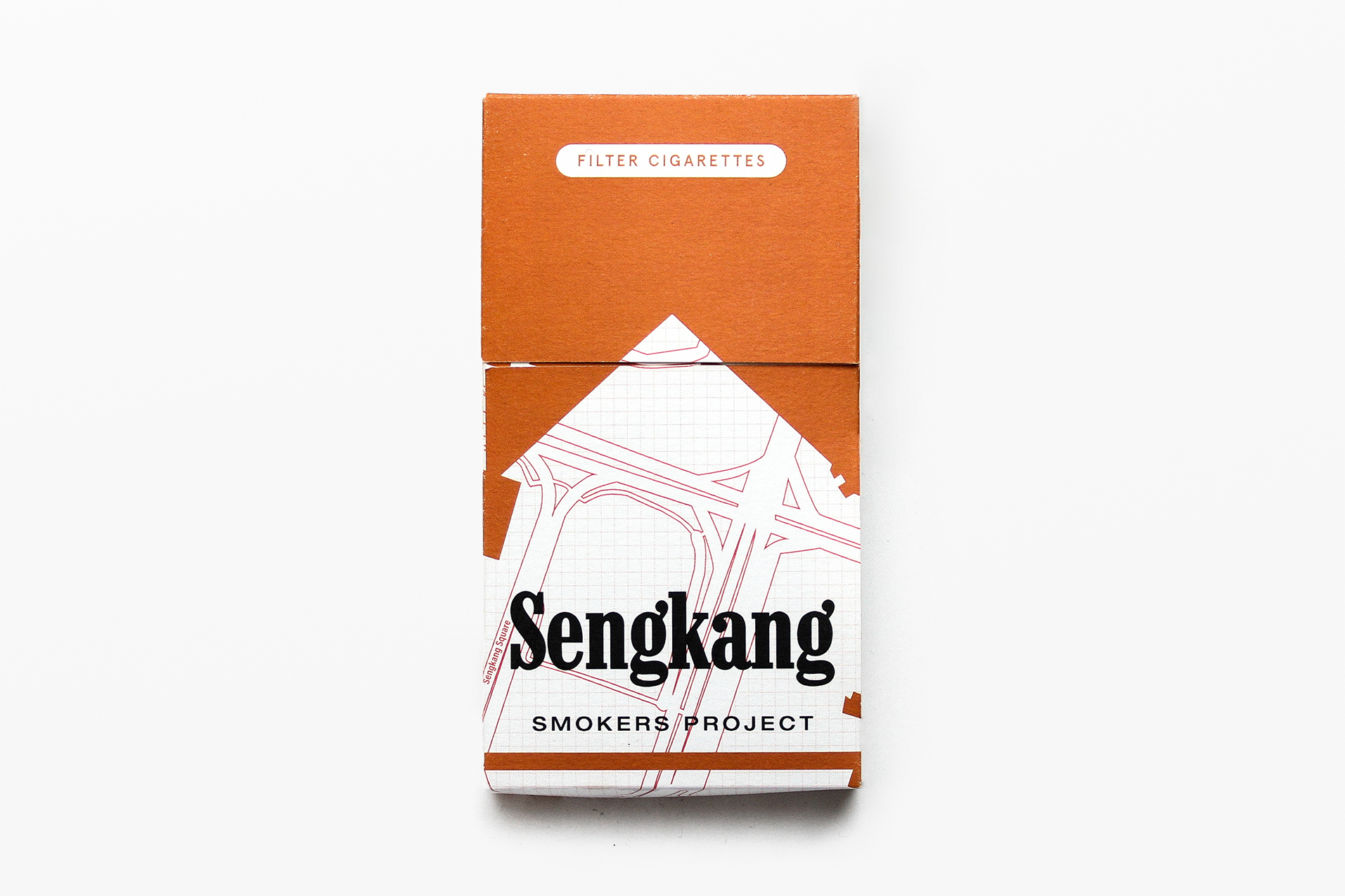

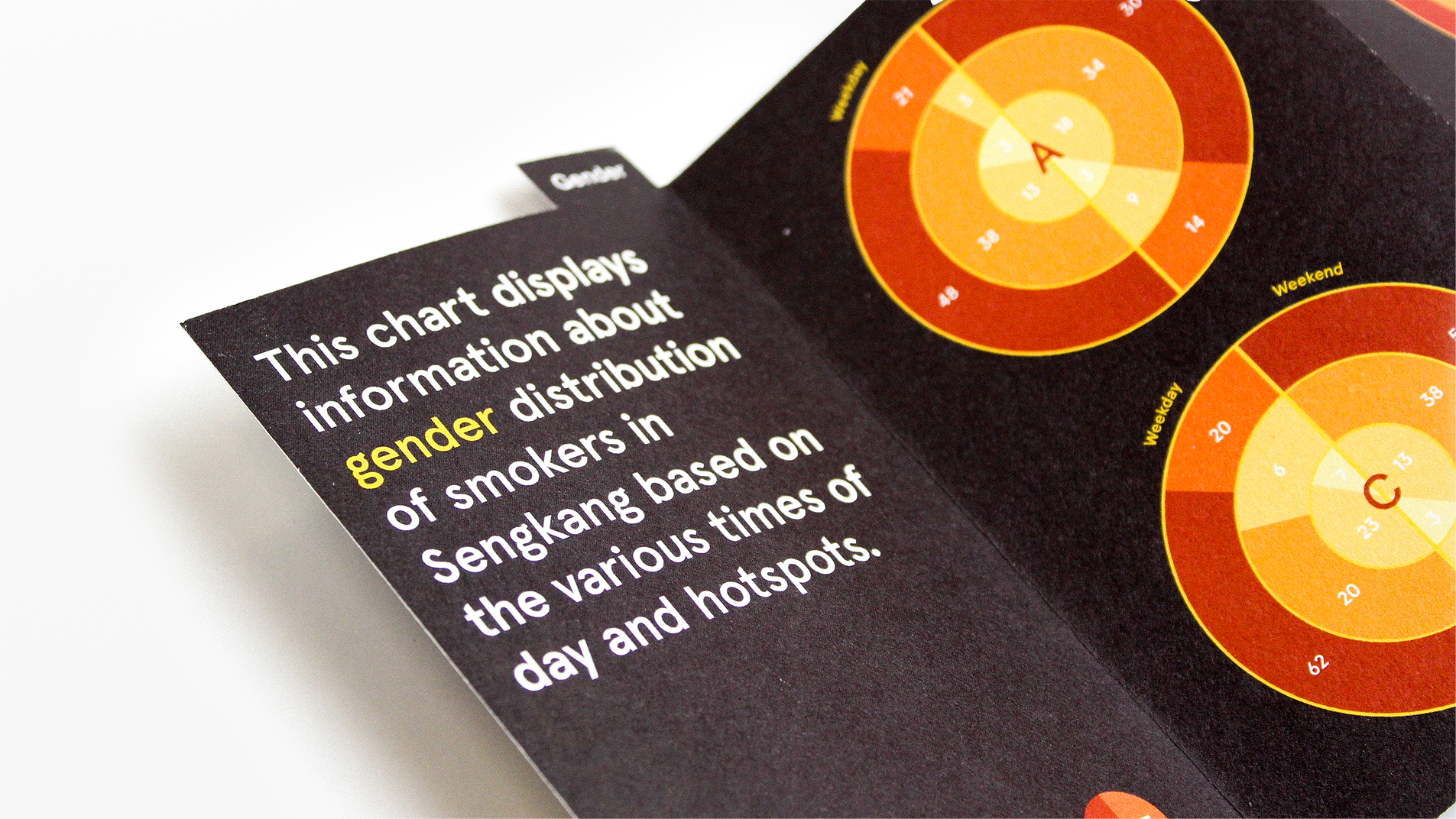

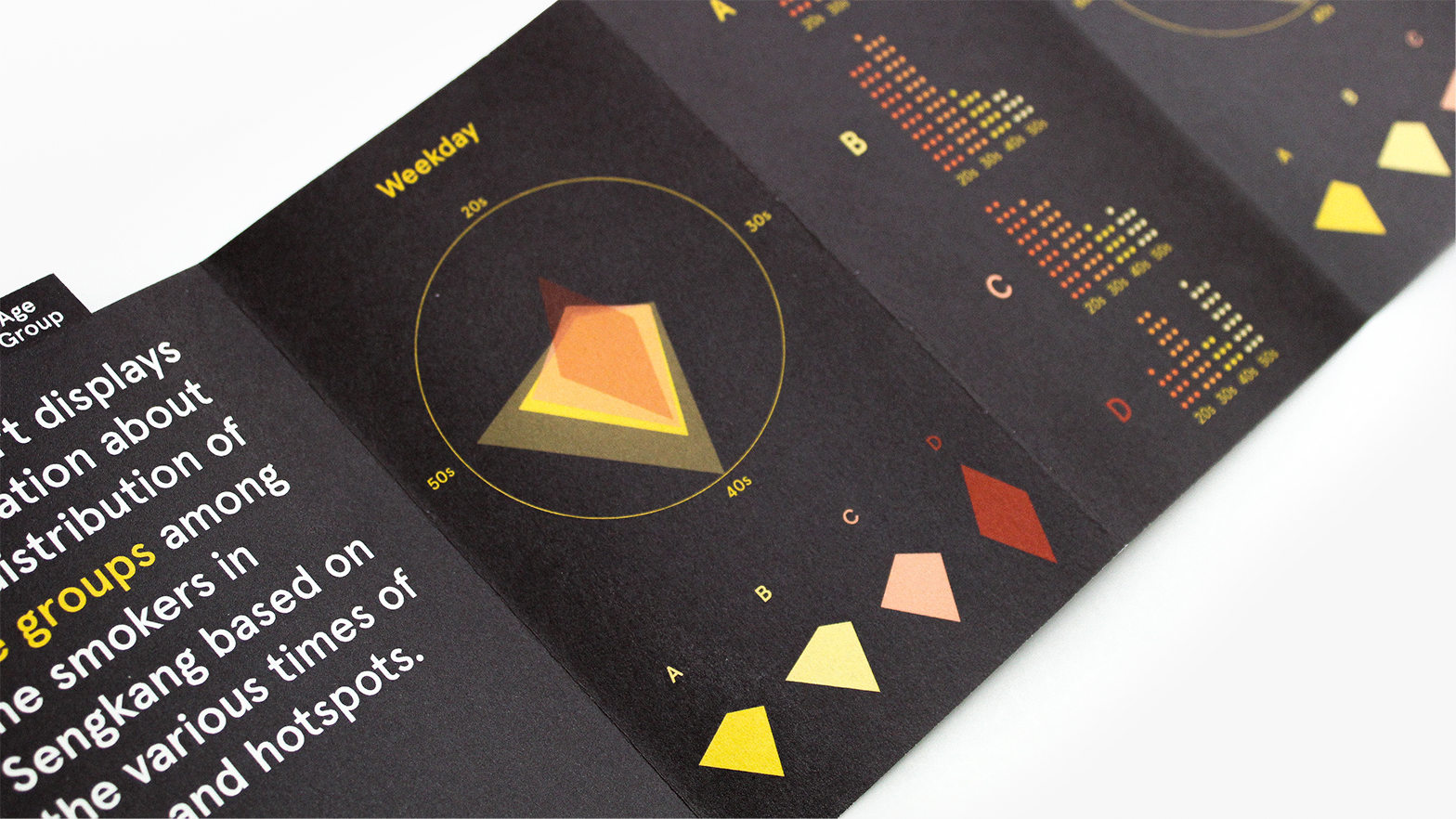

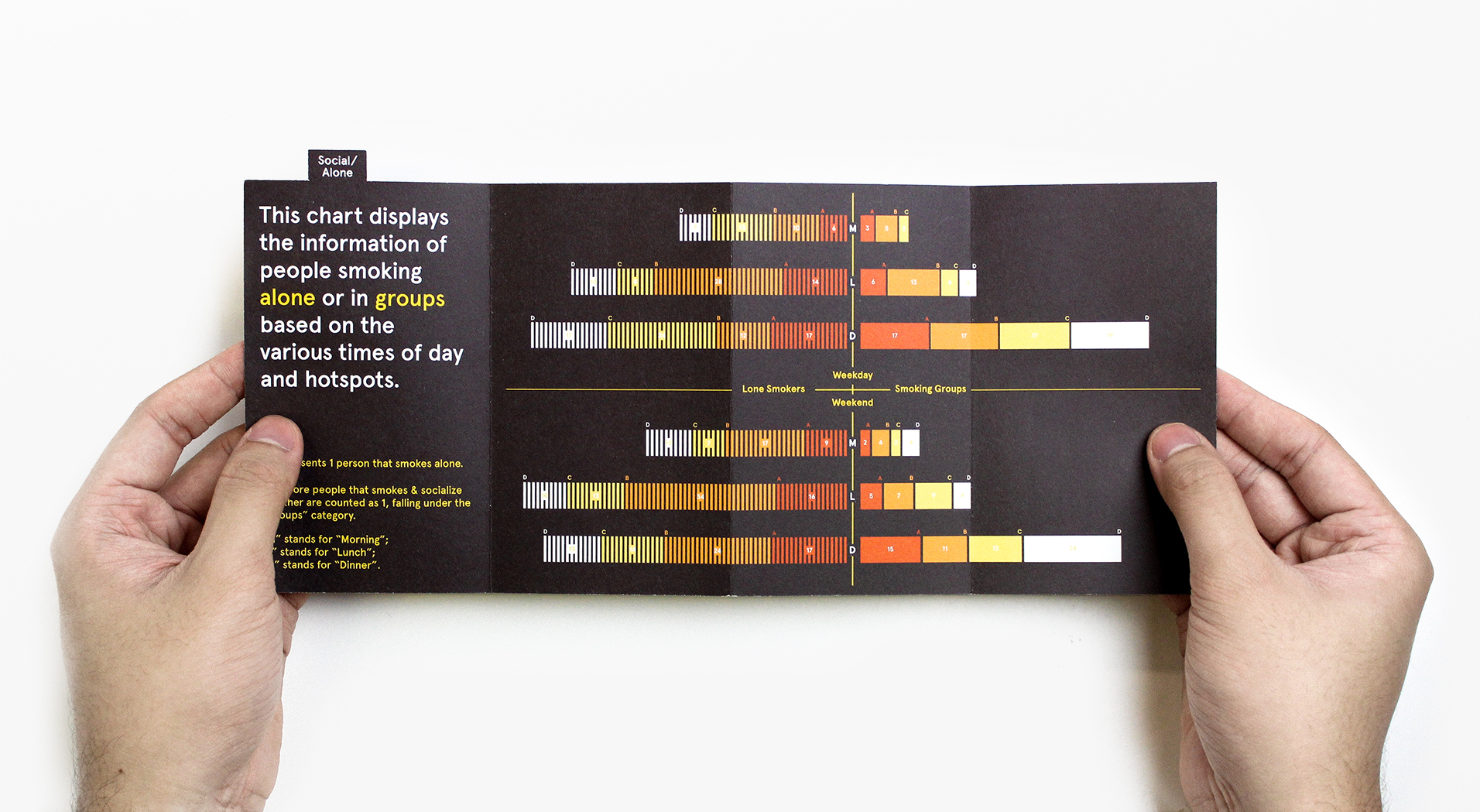

An information design project that inquires into the smoking habits of residents of Sengkang, the youngest neighborhood in Singapore.

An information design project that inquires into the smoking habits of residents of Sengkang, the youngest neighborhood in Singapore.

On-site observations were conducted around the Sengkang neighbourhood for the duration of 6 weeks, where multiple data points such as time, gender, age group, duration, and sociality of the observed smokers were collected and fed into data visualization tools.

Leaflets containing information about the project, such as Research Methodology, Site Information, and Objectives, are housed in a cigarette-inspired box which can be dismantled to reveal an illustrated map of the neighbourhood.

As a finishing touch, the paper stocks used in the project is rubbed with real tobaccos from unused cigarettes prior to printing, adding a layer of sensorial experience for the audience to engage with the project.

As a finishing touch, the paper stocks used in the project is rubbed with real tobaccos from unused cigarettes prior to printing, adding a layer of sensorial experience for the audience to engage with the project.

A simple minisite was also created to present gathered and visualized data on a digital format, with the goal to increase the reach and accessibility of the project.